The Sybarites: Fruit of the Vine

Roderick Conway Morris (The Spectator 5th March 2011)

According to Athenaeus of Naucratis, the 2nd-century AD author of The Sophists’ Banquet, the ancient Sybarites kept the capital of their city-state in southern Italy supplied with wine through a network of ‘vinoducts’ that reached far out into the surrounding countryside.

Amusing though this high-table story was, it reflects the extent to which ancient Mediterranean civilisations were fuelled by the fermented grape, a sacred fluid central to the imagery and practice of Judaism and Christianity. The origins of wine and its role in inspiring antique religion, philosophy, science, commerce, culture and social life are the subject of Vinum Nostrum, curated by Giovanni di Pasquale, a sequel to the diverting exhibition The Ancient Garden from Babylon to Rome, staged in the Orangery of the Pitti Palace in the Boboli Gardens three years ago.

The vine, a wild climbing-plant, seems to have been one of the first crops to be cultivated by mankind. And Georgia provides the first evidence of this going back over 8,000 years. Clay wine cups from the National Museum in Tbilisi at the opening of the show date from the 6th and mid-3rd millennia BC.

The standard tipple of both Mesopotamian and Egyptian civilisation was beer but wine became the drink of the ruling classes. Egyptian gods drank wine, while the Greek Olympian deities stuck to nectar. Possibly the first recorded juvenile binge drinker features in some Egyptian tomb murals at El-Kab — a young girl demanding 18 jugs of wine with the expressed intention of getting wasted.

An alabaster frieze of Assurbanipal (668–631 BC) from Nineveh shows him with his queen drinking wine beneath a pergola of hanging grapes supported on trees, the festivities occasioned by the defeat of an enemy whose decapitated head can be seen decoratively suspended nearby. (There is a cast of the frieze here, while the original can be admired in the British Museum.)

This system of ‘marrying’ vines and trees was employed by the Etruscans and in Campania, and is still to be found in southern Italy and Portugal. It was ideal for mixed agricultural systems, keeping the fruit out of reach of grazing livestock — and is the scenario that lies behind Aesop’s fable of ‘The Fox and the Grapes’. The Oenotrians, who crossed the Adriatic into southern Italy around 1500 BC, seem to have got their name from ‘oenotron’, or wine stake, which they used (then an unusual practice) to plant their vineyards.

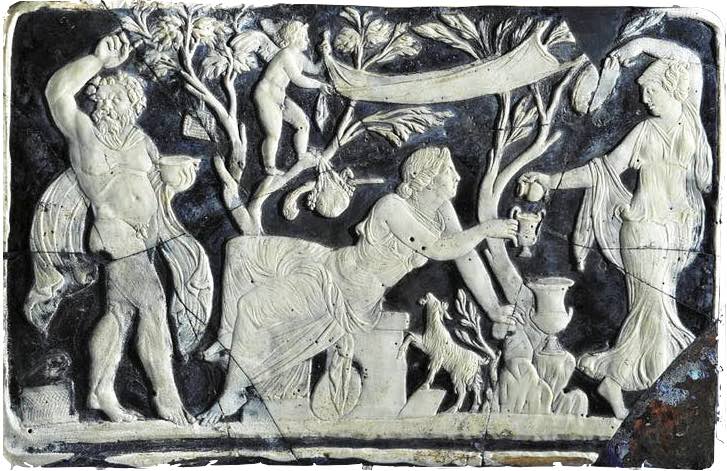

The symposium (‘drinking together’) became the heart of Greek intellectual life and even stimulated the study of hydraulics. Various cunning jugs and vessels (working models of which have been constructed for the exhibition) were designed to dispense wine and water or mix the two and delight the company with their mechanical tricks.

At the Greek symposium, after perhaps an initial full-strength hit from a small jug, or oenochoe (wine-pourer), wine was always diluted with water in a crater (the memory of this survives in the Modern Greek word for wine, krasi, which originally meant a mixture of wine and water). Only Barbarians, in Greek eyes, would spend a whole session drinking the stuff neat (which did not prevent many a Hellenic symposium ending in drunken disorder). According to Athenaeus of Naucratis’ health warnings, drinking straight wine could lead to madness and paralysis.

There is a fascinating line-up here of vases and panels illustrating the symposium in its Greek, Etruscan and Roman manifestations, and examples of all the vessels and equipment involved, including craters, jugs, bowls and glasses, and cooking gear, such as kebab skewers, casseroles and cheese graters (some of this metalwork, from as early as the 6th–4th century BC, in remarkable states of preservation).

Greek symposiums were strictly male affairs except for the presence of flute-girls, dancers and other sexually available professionals. The 4th-century BC Greek historian Theopompus of Chios recorded with amazement that among the Etruscans ‘the women dine next to anyone they like, toast anybody they want and are great drinkers’.

Early Roman women were in theory prohibited by law from drinking wine (as this would inevitably lead to adultery). But the lingering ban on female consumption of alcohol was clearly honoured above all in the breach by later Republican and Imperial times.

The scale of the ancient wine trade was staggering. Imported Greek wines, such as those from Corinth, Lesbos and Chios, maintained their cachet in the upper echelons of Roman society. But industrial production in Italy made it possible, between the mid-2nd and 1st centuries BC, to export to Gaul alone an estimated 40 million amphora containing over 100,000 hectolitres of wine. A single amphora of 20–30 litres could be exchanged in Gaul for one slave, providing a constant source of manpower for the great Italian wine estates and stupendous profits for their patrician owners. By the Augustan age, pitch-lined wine tankers containing 3,000 litres were plying the seas to provide cheap plonk for the Gaulish market.

An unforeseen consequence of Caesar’s conquests and colonisation was the rise of the home cultivation of vines in Gaul and Spain and a fall in demand for imports. In the late 2nd and early 3rd century AD, a revolution occurred with the wide-scale switch from the amphora, the favoured means of shipping wine for nearly a millennium, to the barrel, a Celtic invention combining the skills of their craftsmen in metal and wood, and the standard bulk wine container ever since.